I just discovered a few weeks ago the weekly Riddler column on FiveThirtyEight, which is about data and math focused problems embedded into entertaining riddles. More precisely I got hooked on one specific problem, the War of Riddler Nation, which popped up again last weekend with an interesting plot twist. I decided to solve it. I’m not sure I managed to but it was fun, even though I missed the deadline for submission.

The Original Wars

So the basic setup is the following (right from the Riddler itself):

In a distant, war-torn land, there are 10 castles. There are two warlords: you and your archenemy, with whom you’re competing to collect the most victory points. Each castle has its own strategic value for a would-be conqueror. Specifically, the castles are worth 1, 2, 3, …, 9, and 10 victory points. You and your enemy each have 100 soldiers to distribute, any way you like, to fight at any of the 10 castles. Whoever sends more soldiers to a given castle conquers that castle and wins its victory points. If you each send the same number of troops, you split the points. You don’t know what distribution of forces your enemy has chosen until the battles begin. Whoever wins the most points wins the war.

So what would be your strategy? How would you divide your forces between the castles?

Of course there is no single winning strategy which beats all the others all the time, but by collecting all the submissions and simulating every “war” between all the possible pairings, a winner emerged, whose strategy (3, 5, 8, 10, 13, 1, 26, 30, 2, 2) won more than 80 percent of the wars. (Here are the results of that round.)

Enter the Spy

Last weekend the story got a little twist, when a spy entered the scene. It has a huge advantage: the warlord commanding the spy has complete knowledge of the enemy’s strategy (how many soldiers will be sent to each castle). On the other hand due to some earlier battles he has much less soldiers. The question: how many soldiers is the spy worth, meaning what’s the required minimum amount of soldiers that can win the war together with the spy, no matter what the enemy does?

How many is enough?

As I’m in the middle of my data science ‘studies’, I decided to attack with code (maybe trying to think a little more before hitting the keyboard would have saved some time, but hey, thinking is not my style!).

First, how to decide what is the required minimum number of soldiers against any given enemy strategy which guarantees winning the war (earning at least 28 points)?

Basically it’s a value investment question with some constraints: you want to ‘buy’ enough (but not too many) points with spending the least amount of resources (soldiers) by going for the ‘cheapest’ points on the field. So I tried to create some elaborate methods with calculating the relative value of each castle (a great measurment is the soldiers spent divided by the number of points earned, just like a P/E ratio of a stock), but I just overcomplicated the whole thing.

(One assumption emerged from it: there’s no point in going for a draw at any castles. You just save one soldier compared to winning the battle, but lose half of the possible points. Investing that one little soldier gives the best ROI (return on investment), so why not make it? This might be a false assumption (there could be scenarios where it does make sense to gain just half of a castle), but it least makes the whole simulation easier.)

So I went for the brute force. Got all the 4, 5, 6 and 7 member combinations of the castles, calculated the potential cost of winning the castles in each combination (based on the number of enemy soldiers), and picked the one that gives at least 28 points for the least total cost. That’s about 20 lines of code even in my gibberish coding style.

from itertools import combinations

# Get all the possible 4,5,6,7 castle combinations (792 in total)

COMBOS = []

for n in range(4, 8):

COMBOS += combinations(range(10), n)

def get_minimal_required_soldiers(enemy):

# Cost of winning for each castle

cost = [soldiers + 1 for soldiers in enemy]

# Point value of the castles

points = range(1, 11)

# Calculate the point value of each combination

combi_values = []

for combination in COMBOS:

point_value = 0

soldier_cost = 0

for castle_index in combination:

point_value += points[castle_index]

soldier_cost += cost[castle_index]

combi_values.append((point_value, soldier_cost, combination))

# Get the combination with the lowest cost from those that give enough points

eligible_combinations = [combi for combi in combi_values if combi[0] >= 28]

min_cost_strategy = min(eligible_combinations, key=lambda x: x[1])

winner_castles = min_cost_strategy[2]

# Transform attacked castles tuple to full list of soldier allocation

allocation = []

for idx in range(10):

if idx in winner_castles:

allocation.append(cost[idx])

else:

allocation.append(0)

return {

'opponent_soldiers': enemy,

'allocated_soldiers': allocation,

'soldiers_required': sum(allocation)

}

How many do we need?

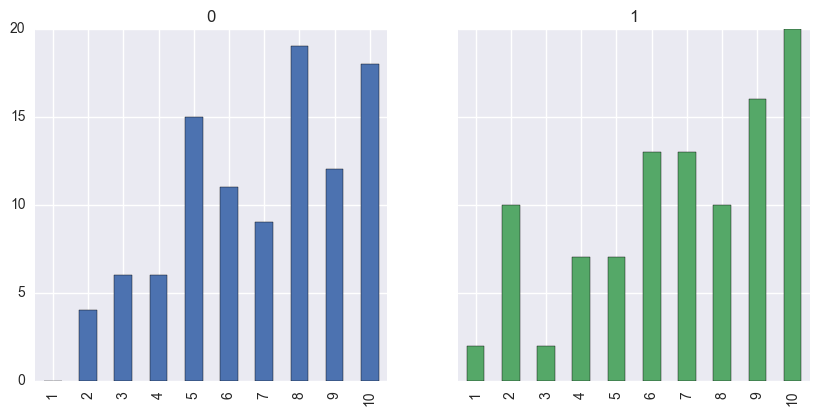

Then I used a little more brute force. I generated a bunch of random(ish) enemy strategies, and used the logic above to decide how many soldiers are required to beat these strategies. In a sample of 115 000 random setups I only found two that required at least 47 soldiers, all the others needed less. Here they are:

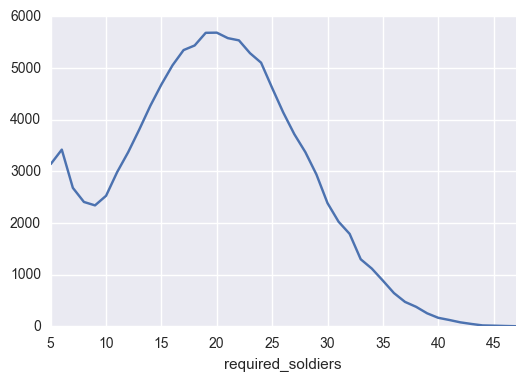

Obviously this sample is a tiny fraction of all the possible combinations so statistically speaking this solution is not sound (and it might be biased by the assumption about draws), but for the time being I stand with the result of 47 soldiers.

In other words a spy is worth 53 soldiers.

(Actually it’s worth more: based on the sample you can win 90 percent of the possible wars with only 30 soldiers, and with as little army as 26 soldiers the winning rate would still be 80 percent.)

(Cover photo by Teddy Kelley on Unsplash)